HOMEWesley Britton’s Books,

|

Spies on FilmSpies on Television & RadioSpies in History & LiteratureThe James Bond Files |

|

Spies in History & Literature ~ An Emerging Trend in Spy

Fiction – Retired James Bonds Become Ian Flemings

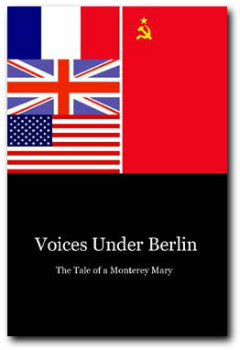

By Mark T. Hooker In 1994, in his spy novel Last Train from Berlin, W.T. Tyler – a retired Foreign Service officer – characterized one of the retired CIA officers populating his book as “little more than a ghost now, prowling his Georgetown house, pretending fulfillment in the imaginary companionship of his imaginary book” (p. 65). In the twenty-first century, however, spy fiction by retired intelligence professionals is no longer the stuff of imaginary books. These days, there are enough books by retired insiders to speak of a trend in spy fiction, or perhaps even of a subgenre. In his article for the New York Times in March 2005 entitled “Ex-Spies Tell It All,” Scott Shane speaks of the “swelling library of increasingly candid CIA memoirs” which paints a portrait of the CIA that “is none too flattering.” (Note 1) Big-splash nonfiction memoirs are finding a ready reception in publishing houses and movie studios with deep pockets for publicity. Insiders’ spy fiction, however, is often hard to locate, as if these kinds of novels – just as their authors once were – are under cover, reflecting the reluctance of traditional publishers to take on these projects. This new spy fiction trend is, therefore, perhaps best visible on the book review webpage of the AFIO (Association For Intelligence Officers). (Note 2) There, one can find novels from publishing houses whose names do not have the recognition factor of conventional publishing power houses such as Brassey’s Books, Forge Books, William Morrow, and Random House. This new class of books is from publishers with names like Xlibris, Infinity Publishing, First Books Library, and iUniverse. Books from these houses do not get the same kind of editorial push to marketability as books from the big-name houses, so, if there is an agenda in the book, it is the author’s and not the publishers. The conventional wisdom that traditional publishers are the best judges of the public’s taste in the literary marketplace is starting to give way to success stories of independently published books like A Train to Potevka: An American Spy in Russia, which has sold over 150,000 copies and whose author has a motion picture contract in hand. And Voices Under Berlin: The Tale of a Monterey Mary, which was an award winner at the 2008 Hollywood Book Festival. The developing trend in spy fiction that they represent is only just beginning to be identified by inquisitive spy fiction researchers. To give the reader a feel for the substance of this emerging trend in spy fiction, this review will take a look at four of the books that are a part of it. Though they are part of a trend, the books themselves are all uniquely different. One is a HUMINT procedural, with a drama worthy of a Greek tragedy. (Note 3) One is a psychological study of a case officer’s last tour, with a happy ending. One is the tale of a covert action gone awry. And last, but not least, there is a representative of that rarest species of spy fiction – a SIGINT novel. (Note 4) James Bond’s “Brothers” Perhaps because 2008 is the centenary of Ian Fleming’s birth, interviews with these authors invariably compare their stories to those of Fleming’s James Bond, whose Hollywood adventures were stretched beyond the bounds of Fleming’s books to create the larger-than-life Bond of the silver screen. The title of an article about A Train to Potevka in The Costco Connection plays on the familiarity of James Bond’s hallmark introduction – “Bond, James Bond.” The article is entitled “Ramsdell, Mike Ramsdell – Reality is as compelling as fiction for real-life James Bond”. In the article, Ramsdell concedes that Bond’s movie adventures were what initially made him want to become a spy. T.H.E. Hill (Voices Under Berlin) makes a similar admission, specifically blaming Sean Connery for the way that he portrayed Bond in the movie Dr. No (1962) as the reason he entered intelligence work. (Note 5) In the movie Tomorrow Never Dies (1997), Miss Moneypenny calls Bond a “cunning linguist” on the phone when she speaks to him in Oxford, where he is brushing up his Danish under the tutelage of a voluptuous instructor in a state of undress. Ramsdell, Murphy, and Hill all learned Russian in the military. “Military linguists have been calling themselves ‘cunning linguists’ since long before Miss Moneypenny made the term popular in the movie Tomorrow Never Dies,” said Hill. “None of my instructors ever looked like that, and we never did any role-playing with the set of vocabulary that Bond was practicing in the movie.” Hill speculated that one of the script writers must have been a military linguist “in another life”. (Note 6) Ramsdell, Murphy, Coyle, and Hill are quick to point out that real-life spying is a far cry from Bond’s action-packed screen adventures, liberally decorated with dazzlingly attractive fold-out girls. As Ramsdell says in A Train to Potevka, “actual intelligence work is far removed from the ‘cloak and dagger spies’ portrayed in Hollywood. . . In reality, intelligence work is extremely serious, tedious, and unglamorous” (p. 205). “One of the key features of Voices Under Berlin,” says Hill, “is the boredom inherent in any intercept operation while waiting for the target’s proverbial loose lips to provide the information that will sink a proverbial ship.” In Hill’s novel, boredom takes on a role similar to the one it played in Thomas Heggen’s Mister Roberts. To relieve their boredom, the Americans play practical jokes on one another and on the hapless East-German guards in a tower across the border. In The Dream Merchant of Lisbon, Coyle has his hero come in to his embassy office during lunch so that he will not be disturbed while he catches “up on his financial accountings and other non-glamorous administrative aspects of being an intel officer.” The narrator quips that Reilly had “seen every James Bond movie ever made and never once had [Bond] ever had to file an accounting.” (p. 254) The world that Reilly lives in, says the narrator, is “not the fantasy world of books and movies, but the shadowy real world where you recruited people to spy, helped overthrow governments and sometimes people died.” (p. 10) “I think Ian Fleming intended [Bond] as a spoof, and people took it as reality,” says Murphy in an interview in The Northeast Times. “It’s really the farthest thing from reality.” (Note 7) The gap between the fantasy of James Bond’s screen adventures and the reality of day-to-day espionage as seen by these authors means that the new “reality” spy fiction may not appeal to “thriller” fans. The stories that these authors have to tell are not the stories of James Bond, Jack Ryan, or Jason Bourne. They are the stories of real intelligence officers, and those are not quite as action-packed. Seeking the Truth  Thomas Murphy (Edge of Allegiance) spent a quarter of a century – 14 years of that overseas – with the CIA before retiring in 1992. (Note 8) Edge of Allegiance is the fictional postmortem of a failed Cold-War HUMINT operation that the author calls the Bagatelle case. It takes the reader from Rio de Janeiro, to Washington and Moscow, from Budapest to Vienna, Prague, and Paris, following the source (Bagatelle) and his case officer (Frank Manion), while the narrator explains where and why things went wrong. By the time the narrator had found the answers to his questions, “[i]t was too late to restore reputations,” or “raise the dead.” The reason that the narrator gives for continuing his quest despite its apparent futility is found in the quotation from the Gospel according to John that is to be seen at the main entrance to the CIA – “And you shall know the truth, and the truth will set you free.” (p. 2) Murphy’s narrator wanted to learn the truth. As W.T. Tyler says in his novel, Last Train from Berlin, the truth isn’t “what you begin with but what you discover” (p. 369). The process of discovering the truth from Murphy is well worth the effort. The narration of the novel deceptively speeds up the glacial movement of a HUMINT operation the same way that a naturalist filmmaker compresses the blooming of a flower into a one-minute segment of action. The nine months of a Hungarian language course is bridged with a single Christmas party episode. The week-long tedium of waiting for an asset to show up is skillfully covered in a single paragraph. The result is as readable as the filmmaker’s stop-action movie of a blooming flower is viewable. While Murphy quite correctly says that Edge of Allegiance “is not a boom and bang thriller,” it is a page-turner. More than half of those who posted reviews of Edge of Allegiance on Amazon.com said that they were looking forward to reading another novel by Murphy with the same characters. The language is lively, and the jargon authentic; the Russian cursing especially so. For those who have been there and done that, the dialogue and the action immediately feel as comfortable as a pair of well broken-in shoes. For those who have never been there or done that, this is what it is really like. Murphy does a good job of defining the fault lines between headquarters culture in Washington and the culture of those who work in the field, and it is abundantly clear on which side of that line Murphy’s allegiances lie. He describes headquarters as a “bureaucratic treadmill” (p. 161), where everyone is “looking over your shoulder” (p. 200). His most telling criticism though, is of the jaundiced attitude towards field officers that is held by headquarters officers, who, he notes, “would have little to do” without the officers in the field who make recruitments. (p. 67) Escape, Evasion, and Survival  Mike Ramsdell (A Train to Potevka) served as a Military Intelligence (MI) officer, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel before his retirement. His uniformed and civilian career took him throughout Europe, Russia, Scandinavia, and to Asia. A Train to Potevka is a tale of escape and evasion aboard a train traveling across the vast frozen wastes of Siberia following the collapse of a covert operation. Ramsdell’s train is not, however, the luxurious train of Agatha Christie’s snow-bound Orient Express, but an ice-encrusted, third-class milk-train with hard seats, no heating, and no food that a foreigner can ingest safely. Ramsdell’s writing style is not going to make him the new Hemingway, Fleming, or Pasternak, but the reason for the book’s popularity is clear. It is a tale of survival, written with enough of an adventurous edge to make you want to keep reading to find out how the author lived through the events described in it. It’s not edge-of-your-seat excitement, but that’s not the intent. On the one hand, it has the atmosphere of the icy adventure of Jack London’s “To Build a Fire,” and, on the other, a sense of the spiritual depth of Alexander Solzhenytsyn’s One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich, which is likewise a tale of a battle with the Siberian cold. A Train to Potevka is a story of individual survival in a battle with the forces of nature, and of the value of small achievements in the face of grindingly depressing circumstances. In other words, it is not great literature with a capital “L”, but it is a great story. One reviewer on Amazon.com seems to have captured exactly the right description of Ramsdell’s writing by comparing the reading of A Train to Potevka to “listening to war stories told by a favorite uncle.” An episode in Ramsdell’s tale that will bring a smile to the face of many a hard-boiled veteran of a tour inside the Iron Curtain is Ramsdell’s story of treating his Russian surveillance to a take-out meal from McDonald’s when the surveillance couldn’t buck the line like Ramsdell (a foreigner) could. It is a story that there are a hundred variations of, but one that is nevertheless a pleasure to hear again and again, because it restores one’s faith in the inherent goodness of the intelligence officers who took pity on their surveillance, and did something nice for them. The Hollywood James Bond would never have done something like that. Typical for this new trend in spy fiction, Ramsdell addresses the culture clash between HQs and the field. In Ramsdell’s novel, this thread of the story has an almost “fairy tale” happy ending, in which the members of “the Good Old Boy Washington Establishment” who put his life in danger find themselves “in serious trouble.” (p. 267) His treatment of this topic is the least realistic of the four. Leaving the Game  Gene Coyle (The Dream Merchant of Lisbon) retired in 2005 with 29 years of service, almost half of which was spent overseas, including a tour in Moscow. He is a recipient of the Intelligence Medal of Merit. The Dream Merchant of Lisbon is a psychological study of two intelligence officers on their last overseas tour. One of them is the CIA case officer Shawn Reilly. The other is Boris Sergeevich Parshenko, the SVR (KGB) Resident in Lisbon. Both of them have to decide what they are going to do once their tours are over and they can no longer play the game of espionage. Along the way Coyle paints a realistic picture of how a case is handled. The case that Reilly is handling is, of course, Parshenko, code-named FOX. Parshenko has decided that retirement in California is more to his liking than retirement in Moscow. Parshenko does not intend to take his wife with him into retirement, and Reilly thinks to himself about how many broken marriages there have been. He thinks to himself that “there would probably be an Oprah show one day – the abandoned wives of Russian intelligence officers.” (p. 149) Reilly is not in much better shape himself. His wife is divorcing him, and he has no idea what he wants to do when his tour in Lisbon is over. The lives of the two men neatly mirror each other as the novel progresses to its surprise conclusion that recalls some aspects of Hopscotch (Brian Garfield, 1975). Coyle, like Murphy, devotes a considerable amount of time to the issue of the divide between headquarters culture in Washington and the culture of those who work in the field. Coyle complements his descriptions of the CIA’s bureaucracy with descriptions of the SVR’s. The narrator says that Reilly would have had a better career with the CIA, if he had “concentrated more on the bureaucratic side of the business and taken management positions” behind a desk, “but he was a street case officer at heart.” (p. 11) In his final confrontation with his Chief of Station, Reilly says, “I’ve always had trouble seeing the difference between a team player and kiss-ass – thanks for giving me an example.” (p. 257) One of Parshenko’s many complaints about SVR HQs is that “the bastards” back at Moscow Center “have nothing to do,” but they just sent him a cable informing him that his end-of-the-year reports were submitted in the wrong format, and he has to do them over. As if he does not have anything better to do. (p. 236) Coyle has a slightly more pointed parallel to Murphy’s question of “is there intelligent life at HQs?”. When HQs sends out a message advising the Station how to handle the Parshenko case, Reilly comments ironically that he “always loved reading the views of CIC, an office full of experts who had never recruited or handled an agent in their entire careers.” (p. 69) The Ultimate Eavesdropping  T.H.E. Hill (Voices Under Berlin) retired in 1993 after 26 years of combined uniformed and civilian service, 16 of it overseas. Voices Under Berlin is a fictionalized look at the CIA cross-sector cable-tap tunnel in the Rudow district of Berlin, perhaps better known as Operation GOLD (code name: PBJOINTLY). Hill’s novel is ostensibly the story of the American soldiers who worked the tunnel, and how they fought for a sense of purpose against boredom and the enemy both within and without. It is told with a pace and a black humor reminiscent of that used by Joseph Heller (Catch-22) and Richard Hooker (M*A*S*H*). The writing style used in the novel, however, is unique. It demonstrates an unusual approach to literature that reminds the reader of Henrik Ibsen’s “play for voices,” Peer Gynt. This play is usually considered very hard to stage due to its accent on the aural, rather than on the visual. The novel is likewise almost totally lacking the kind of visual clues that readers are accustomed to seeing on the printed page. Instead – as the novel’s title (Voices Under Berlin) suggests – it is a novel of voices, intended as a tale to be heard. Half the novel is made up of unnarrated transcripts of conversations between the Russians whose telephone lines have been tapped. The other half of the novel carries the same “aural” signature as the transcripts, reflecting the ear-centric worldview of the people who had to transcribe the Russians’ conversations. The result is a new type of spy novel, as unique as Berlin herself. The faulty transcription of one of the Russians’ calls takes the world to the brink of war. Can the mistake it contains be corrected before the Cold War goes hot? “And why is this man transcribing a tape in his underwear?” asks Lieutenant Sheerluck, oblivious to the fact that they are teetering on the razor edge of the line between war and peace. When the novel ends, the reader is left pondering a question that is common to all four of the novels in this review. Who were really the victors and who the vanquished in this battle of wits? History says the Russians won, but were they the real enemy, or were they just the target of the tunnel operation? The novel’s answer is much more subtly presented than it is in the other three books. Though Voices Under Berlin is set in the 1950s, one reviewer on Amazon.com characterized it as “relevant for today,” because the skill set that the hero possesses is the one that helped to win the Cold War. The reviewer says that this is the same set of skills that we still need today to win the war on Terror. A similar comment is found in one of the Amazon.com reviews of Edge of Allegiance. There is clearly more than just a “war story” woven into the warp of words in these novels. Beyond the Mainstream The words of these four novels may not speak to publishers’ and literary agents’ perceptions of what it takes to put their bottom line in the black in the dog-eat-dog modern literary marketplace, but they do speak to those interested in the reality of the human condition of America’s spies, rather than in the literary and silver-screen representation of it. Read one or more of these novels and see for yourself. Mark T. Hooker is a specialist in Comparative Translation at Indiana University’s Russian and East-European Institute. Retired, he conducts research for publication. He is the author of “The Military Uses of Literature: Fiction and the Armed Forces in the Soviet Union,” an analysis of works of literary fiction written by serving and retired Russian military officers and “Tolkien Through Russian Eyes,” an analysis of the nine Russian translations of The Lord of the Rings. He is a graduate of the U.S. Army Russian Institute (USARI) at Garmisch-Partenkirschen, Germany. Notes ~ Note 1 – “Ex-Spies Tell It All”, by Scott Shane; New York Times, Published: March 15, 2005 Note 2 – Association for Intelligence Officers, Book Reviews by AFIO Authors. Note 3 – HUMINT = Human Intelligence, i.e. the source is a human being. Note 4 – SIGINT = Signals Intelligence, i.e. the source is an intercepted message. Note 5 – J. Rentilly, The Costco Connection, December 2007, p. 33. Note 6 – “T.H.E. Hill’s Voices Under Berlin – A Spy Novel That Breaks All the Molds”, by Wesley Britton, located in the Spies in History & Literature section of this website. Note 7 – “This spy came in from the cold”, by William Kenny, Times Staff Writer, Northeast Times, Dec. 15, 2005. Note 8 – Not to be confused with David E. Murphy, one of the co-authors of Battleground Berlin: CIA vs. KGB in the Cold War, Yale University Press, 1997. |